When NATO was created, its goal was to coordinate and respond to a Soviet aggression against any member of the Atlantic Alliance; similarly, the USSR established the Warsaw Pact, which faded after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. This distinctive fact was what temporarily transformed the nature of NATO.

It shifted from a defensive anti-communist military organization to an organization that integrated Eastern countries into the Western bloc. NATO’s entry began to prioritize its political aspect over the military, aiming to secure Western influence in the former USSR countries in Eastern Europe and the Baltic, reinforcing the establishment of «democratic freedoms and a liberal market economy.»

NATO, startled by Lukashenko’s rise to power in Belarus, which disrupted the pace of integration guiding Minsk, quickly moved to incorporate these countries into a framework of political and military organizations aligned with the interests of the United States and Brussels, generating substantial benefits for Pentagon coffers through the desovietization and modernization of their armies.

The «Finnishization» strategy involved Western countries maintaining their democratic institutionalism and liberal market while simultaneously trying not to antagonize Moscow over various sovereignty issues; paradigms included Finland (hence «Finnishization»), Sweden, and Austria. Following the fall of the USSR and between 1991 and 2022, the governments of Stockholm and Helsinki saw no need to enhance their international participation in the Atlantic coalition since neither Russia was a threat as the USSR once was, nor did the West need to bolster anything in these countries.

However, with the Special Military Operation, which paradoxically left Ukraine vulnerable as it did not join the EU or NATO, Sweden and Finland were admitted, escalating tension in the Baltic.

The Baltic Sea is a strategically semi-closed body of water for Russia, which, despite its size, has the least access to the sea. Its access is discontinuous, as it is facilitated from two enclaves separated by three hostile countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. These countries even engage in discrimination against the Russian minority within their borders and are among the most belligerent toward Russia in all of Europe.

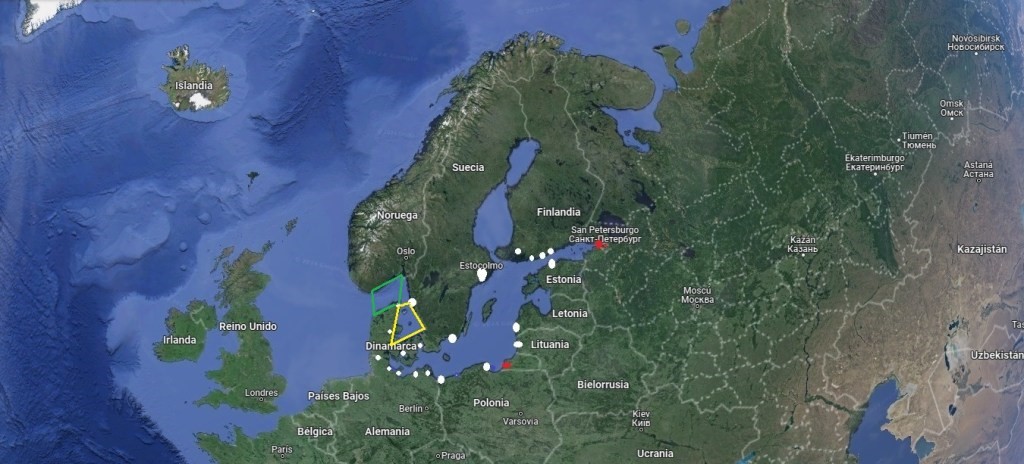

Naval positions of NATO states in white, positions of Russia in red. Skagerrak Strait in green and Kattegat in yellow.

The situation is that the Russian fleet in the Baltic is divided across several bases, adhering to the theory of strategic dispersion: the headquarters in Kaliningrad and military bases in Kronstadt and Baltisk (marked as red points in the Kaliningrad region and St. Petersburg).

As noted, the strategic problem is that access to the sea is limited, dispersed, and the semi-closed sea is a hostile NATO lake. This results in the Russian fleet’s size (with 20,000 vessels) and its naval and amphibious warfare strategy aiming to inflict as much damage as possible. Now let’s look at the enemy points.

Lithuania has a fleet of 700 ships based in Klaipeda; Estonia has its naval operations led from Miinisadam and Tallinn (for the Estonian police and coast guards); Latvia has its naval operations based in Liepaja. These three countries form BALTRON: this squadron emerged from the transfer of vessels from the fleets of Lithuania and Latvia (Estonia withdrew from BALTRON in 2015). Its main goal is to search for and deactivate underwater mines, improve coordination among these countries in naval warfare, and provide constant availability to NATO for military exercises in the Baltic. The bases are marked in green on the map, with BALTRON marked in white.

Estonia’s withdrawal from the minesweeping project and its alignment with NATO demonstrate the seriousness of the issue. However, military buildup involves significant naval forces focused on the Baltic, not only at the naval level but also in coastal defense—thanks to Finland’s and Sweden’s navies.

The Finnish Navy consists of about 6,700 personnel deployed to the Baltic Sea, particularly in the Gulf of Finland, where it has naval bases opposite Estonian territories: the Naval Academy in Suomennlinna, Helsinki, the Nyland Brigade base in Dragsvik, Ekenäs, the coastal brigade based in Upinniemi, Kirkkonummi, and the most crucial, the Baltic coastal fleet based in Panssio, Turku.

With its naval forces within NATO and Baltic countries participating in BALTRON (except for Estonia, which is part of NATO), the Gulf of Finland holds NATO’s coastal supremacy both in its territorial waters during peacetime and in military defense due to the size of these fleets and the capabilities of coastal and anti-air defenses, making it very difficult for Russian naval maneuverability in the area without a combined attack involving naval and land penetration.

Land obstacles, in the form of islands and islets in the region, further complicate matters. Beyond the Gulf of Finland lies the Gulf of Bothnia, which separates Finland and Sweden, both of whom are now NATO allies.

Sweden also takes an internal approach to the Baltic Sea, aside from its 4th Marine Infantry Regiment base in the Kattegat Strait between Jutland and the Scandinavian Peninsula. The rest of the naval power is focused on the Baltic Sea at Karlskrona, where the first submarine flotilla, the third naval warfare flotilla, and the Swedish naval warfare center converge. From this base in Karlskrona, detachments in Gothenburg in the Kattegat are managed, along with the fourth naval warfare flotilla in Berga, together with the 1st Marine Infantry Regiment, which allows for naval and amphibious units. The Swedish Navy’s headquarters is located on Muskö Island.

Poland, focused on the Baltic and having a border with Kaliningrad, has developed a modernized naval warfare strategy for several reasons. Firstly, it is one of the fastest-growing economies in Central Europe, has an active diplomacy, and has modernized its military to the point of being the hegemonic force in the NATO Eastern bloc. Additionally, it shares borders with Belarus and Ukraine, both of which are hot zones for NATO.

This is compounded by a profound hatred among Poles toward Russians, stemming from ultranationalism and the anti-communist stance of the political sectors currently in power in Poland. Statements made by Lech Walesa serve as a clear indication of this animosity and bellicosity. Consequently, Poland boasts a vital structure for naval warfare in the Baltic, with a Maritime Operations Center in Gdynia, housing the Third Ship Flotilla «Commodore Boleslaw Romanowski,» the naval hydrographic office, and the naval aviation brigade. In Świnoujście, the Eighth Coastal Defense Flotilla «Vice Admiral Kazimierz Porebski» is based. From these bases, specialized training schools for non-commissioned officers, officers, and combat lead to naval facilities in Hel and Kołobrzeg.

The German navy, as a key economic driver of the European Union and the strongest country in Europe in terms of economy and industry (excluding Russia), has a naval force divided between the Atlantic Ocean and the Baltic Sea. Here, we will focus exclusively on Germany’s Baltic region.

It has some of the most important bases in Germany. The naval command, its headquarters, is located in Rostock, which oversees the First Flotilla stationed in Kiel, where the naval medical institute is also situated. In Flensburg, Lower Saxony—near Denmark’s border—the naval academy is found, along with the non-commissioned officer academy in Plön and the naval damage control training center in Neustadt in Holstein, all situated in the strategically important northern state of Schleswig-Holstein, a German federal state with double access to the sea and a border with Denmark. The engineering school is located in Stralsund.

In Denmark, the situation is different. Completely secure in its access to the Atlantic Ocean, all its military naval power is concentrated on defending the straits of Kattegat and Skagerrak, making it a narrow funnel. The Danish structure is divided into three squadrons: the first and third squadrons stationed in Frederikshavn for domestic defense, the Arctic Ocean, and Greenland, and for international military tasks such as Operation Atalanta and other international missions. The third squadron is responsible for internal waters and the defense and surveillance of Danish territorial waters. The second squadron in Korsør focuses on international operations and non-combatant evacuation operations, essentially peacekeeping and logistical missions. The Danish Navy’s headquarters is at the Karup air base.

In summary, the Baltic Sea, with the entry of Sweden and Finland and the Ukraine War, has become a NATO lake and a very hot spot in Europe, where the Russian naval disadvantage in a semi-closed operational theater surrounded by hostile forces and with limited maneuverability suggests rising tensions in the area. This is especially true every time military exercises such as BALTROPS are conducted, which have already been heavily scrutinized following the Nord Stream II incident in 2022.

However, (and we will address this later) the naval factor and coastal defenses are not the only elements to consider on this map. The topography of the vast plains of Eastern Europe and the Baltic, which Belarus enjoys as a gigantic flatland, offers certain advantages to Russia on the Baltic Sea front, but also the psychological capacity for a major war, state economies, and the interests of Moscow and NATO to provoke and further escalate the situation in a region that now no longer has a natural balance between the Soviet Union and the West. Instead, the Russian situation and its projection to the sea have diminished despite its gigantic size. In this semi-closed internal sea, one can discern the beginnings of regional geopolitical supremacy that may affect Eastern and Northern Europe, thus highlighting the importance of defending the access to the sea that, since the days of the Duchy of Moscow, the Russians have always sought—whether through the Volga to the Black Sea, expansion into the Caucasus toward the Caspian, or expansion toward the Baltic Sea. It is no coincidence that Peter the Great founded St. Petersburg with a view toward the sea.