One of BRICS’ key principles is “fair multilateralism.” This appeals to many countries that disagree with U.S. unilateralism and the broader Western agenda of maintaining hegemony. This applies not only to the leading countries (China, Russia, India) but also to Global South nations. A significant portion of these are African countries, which see BRICS as a bloc that does not seek to dominate or subjugate them, but rather as an organization based on non-discrimination, dialogue, and consensus. More broadly, it represents an inclusive union that envisions the participation of all countries, regardless of their size or potential, in shaping a fair world order, a system of equal and indivisible security, an equitable and just governance architecture, and a democratic process for formulating and adopting global policy decisions.

Notably, the first expansion of BRICS was marked by the entry of an African country — the Republic of South Africa — in 2011. It is from this point that experts trace the formation of the so-called African vector of BRICS. In the largest expansion wave as of 2024, African countries accounted for nearly half of the new members (Egypt and Ethiopia). Overall, in the current composition, their share approaches one-third, representing a substantial presence. It can be stated with confidence that this presence is likely to grow further, through partnership status and, in the foreseeable future, full BRICS membership. African countries are actively involved in the “outreach” format and several other engagement formats. As early as 2013, during the fifth BRICS summit in Durban, there was a meeting between BRICS leaders, the African Union leadership, and the leaders of eight major African integration organizations. The 2023 summit in Johannesburg, under the motto “BRICS and Africa: Partnership for Shared Accelerated Growth, Sustainable Development, and Inclusive Multilateralism,” reinforced the agenda for deepening and diversifying cooperation. Consequently, African countries figure prominently in both likely scenarios for the evolution of BRICS under the “BRICS Plus” initiative: “BRICS Plus individual countries” and “BRICS Plus continental integration organizations.” It is worth recalling that BRICS supported the African Union’s accession to the G20. In addition, the 2023 summit declared support for South Africa’s candidacy for a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council.

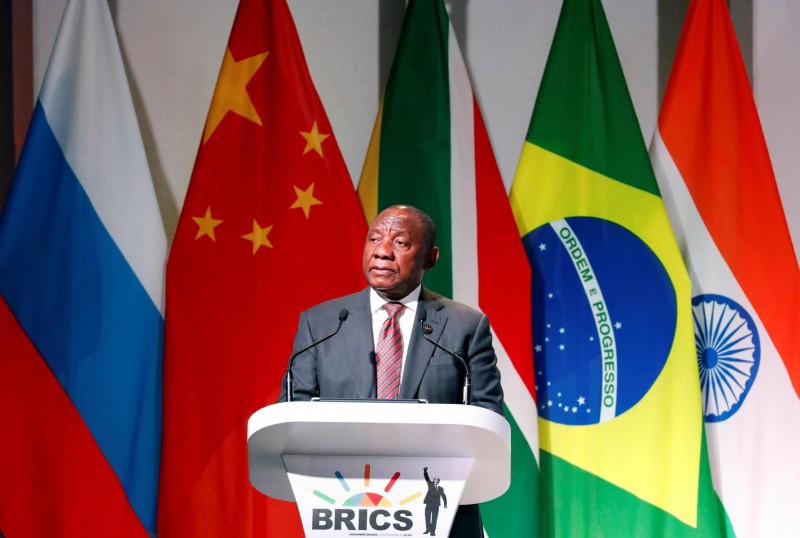

The African agenda within BRICS is also expanding. Initially, the focus on Africa was centered on supporting poverty eradication and infrastructure development across the continent under the NEPAD program. Today, however, the region occupies a special — and, according to experts, largely unique — place in the final declarations. This is evident in the final declaration of the 2024 Kazan Summit, which addresses issues such as African integration, maintaining peace and stability on the continent, and more. The priorities of this agenda are evolving in the context of an ambitious goal by many measures: changing the development trajectory of the Global South, which is increasingly aware not only of its vulnerabilities but also of its special role, responsibilities, and new opportunities to strengthen its own positions, including economically. A promising direction is the participation of African countries in the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB). This allows them not only to receive additional financial support for specific projects (such as ensuring food security, which is extremely urgent for the region) but also to contribute, in one way or another, to initiatives aimed at reforming the global monetary and financial infrastructure, including the trend toward dedollarization. BRICS is widely associated with an alternative to Western institutions. As South African President Cyril Ramaphosa vividly put it, BRICS is a beacon of hope for Global South countries striving for a more equitable global economic system.

Notably, the first African Regional Center was established under the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB). Of course, there are challenges here, including those arising from the economic weakness of some “newcomer” countries, such as Ethiopia. However, significant opportunities also emerge. Africa possesses vast natural and demographic resources (it is expected that by 2050, Africa will account for a quarter of the world’s population) and is showing growth in many economic sectors. Most African countries also demonstrate stable GDP growth, although the dynamics vary. The fastest-growing economies in 2023–2024 include Rwanda, Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, Ethiopia, and Tanzania, with several others approaching similar growth rates. Among the ten largest African economies, three countries are already BRICS members (South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia). Nigeria and Algeria, both rich in natural resources such as oil and gas, have been repeatedly mentioned among interested countries. Other interested countries include Senegal, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Congo, Sudan, Tunisia, Angola, Zimbabwe, and several others, many of which sent delegations to the Kazan Summit. A serious challenge remains the uncertainty of Nigeria’s position — one of Africa’s leading economies — which has yet to submit an official application for BRICS membership.

Overall, promising areas for cooperation between African countries and BRICS may include agriculture; oil and gas; mineral extraction; and information and communication technologies. As instruments, projects under the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB) or bilateral country-to-country projects (e.g., China–Nigeria, etc.) can be utilized. There is also a growing practice of concluding contracts for the construction of industrial facilities and transport infrastructure (chemical plants, railways, etc.), granting concessions for the development of mineral resources (oil, diamonds, uranium, etc.), and activities in the banking sector.

Regarding bilateral cooperation within BRICS, it is important to address the existing imbalance, where China clearly demonstrates economic leadership in implementing various initiatives on the continent, although other BRICS countries — particularly Brazil, India, and Russia — are also increasing their activity. Countries in the region have repeatedly expressed their interest in establishing and deepening investment cooperation.

A less likely but hypothetically possible third option is the development and implementation of political-economic projects involving either regional (African Union) or subregional African integration organizations (e.g., the Southern African Development Community, SADC, which is a priority for South Africa). This could also align with the development of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). Deeper integration would involve reducing import duties and non-tariff barriers for African exports within BRICS. Some projects are being implemented through companies from BRICS countries and subregional organizations themselves—a prominent example is the involvement of the Russian company Prognoz in developing a portal for the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA). BRICS-Africa partnership is supported by the influential pan-African organization, the African Union of Peace and Security (PAPS). At the current stage, due to logistical challenges, BRICS countries also show additional interest in the transport and transshipment potential of African countries, thanks to the availability of convenient seaports.

In the political and socio-humanitarian sphere, attention may be focused on humanitarian assistance as well as supporting peace and security on the continent, although the emphasis is placed on the necessity of independent efforts by Africans themselves. Humanitarian aid is often linked to the promotion of national international development policies. An established form of cooperation is the “debt-for-development” agreements, under which debt owed by African countries is written off in exchange for development initiatives. Russia is active in this area, for example. At the same time, representatives of the political community in African countries currently prefer to focus on investment and other similar projects without direct debt write-offs, restructuring, or similar measures. Contacts are intensifying in several areas, primarily in combating piracy and international terrorism. The situation in the Sahel-Saharan region is of particular concern. BRICS countries are undoubtedly likely to focus on expanding their military presence (through military bases, training centers, private military company activities, etc.), which can also be seen as an additional guarantee of security for African countries. Moreover, they are not perceived by Africans as colonizers, unlike Western countries, which are seen as attempting to regain influence following the collapse of the colonial system, such as France. Other important areas include healthcare (epidemiological security, etc.), combating climate change, and the involvement of women and youth in the economy.

To a large extent, the degree of implementation and effectiveness of political-economic projects depends on the willingness of BRICS countries to combine their efforts, rather than focusing solely on achieving their own objectives. Experts rightly note that each country has certain competitive advantages (China in trade and investment, India in information technology and service sectors, Russia in moral-political authority, technical and technological capabilities, etc.). For overall success, BRICS leaders must focus on projects that represent mutual interest, both for themselves and for specific African countries. A conditional coordination scheme is as follows: first, aligning positions within the group (through summits, specialized forums, meetings of foreign ministers, etc.) and bilaterally; then, thorough project development by expert organizations and competent agencies; and finally, submitting these projects for financing by the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB).

The limitations to cooperation stem from the inherent challenges of the African continent (unresolved conflicts, population poverty, difficult climate and terrain, etc.) and African organizations (institutional and financial weaknesses of the African Union, among others), internal disagreements within BRICS (e.g., China–India tensions, India’s reluctance to strengthen the anti-Western dimension of BRICS activities, etc.), and external opposition (from the U.S., France, the U.K., and others).

Probable Scenarios:

– BRICS as the main donor and sponsor of transformation, sustainable development, and growth in Africa: This scenario implies the scaling up of infrastructure and other projects, supported and implemented at various levels. It correlates with the successful advancement of African integration, achieving a balance of interests within BRICS, and BRICS gaining the status of a genuine alternative to Western institutions.

– Division of spheres of interest and responsibility: In this scenario, BRICS and its member countries would have to accept the continued presence and influence of Western countries, particularly the G7, across the continent and in individual countries. This is associated with certain political and economic challenges for BRICS and its members, disharmony in relations, persistent differentiation among regional integration groups, and the lack of a unified African position based on the African Union.

– Reduction of BRICS and member country presence in Africa, with a Western comeback: This corresponds to the revival of neocolonialism, a loss of BRICS’ attractiveness not only to current or potential partners but also to its own members, degradation of the trend toward macro-regionalization, and undermining the very idea of African integration. In the catastrophic variant, this would entail an expansion of international confrontation, escalation of conflicts and crises, and the defeat of BRICS leaders in geopolitical and geo-economic struggles with the West.

Considering current and medium-term factors, the second scenario appears more plausible. For BRICS and its members, as well as for African countries, the first scenario is preferable. However, its implementation requires the mobilization of resources and efforts, careful planning, sound tactics, and strengthening the trend toward restoring geopolitical balance.